THE SPIRIT MEDIUM

Ubiquitous to the majority of sub-Saharan Africa’s historic cultures, were the specialists in transpersonal or holotrophic consciousness, a term coined by one of the leading psychologists today, Stanislav Grof.

The Spirit Mediums, or N’anga of Zimbabwe were famed throughout sub-Saharan Africa. They played a leading role in the first uprising or chimurenga against the colonialists in the 1890s, and again in the second chimurenga, leading to Zimbabwean Independence in 1980. The Mediums stood for cultural principles which linked the generations through history. The Shona ancestral figure, Mbuya Nehanda, has a history going back ‘thousands of years’ in Zimbabwe, speaking through her chosen Mediums, the last being executed by the colonial Government in 1898 for her role in the first chimurenga.

The Medium is responsible for maintaining the psychological and spiritual balance of society, ensuring that all actions in the community take place according to the transcendent law of relationship, the bed-rock of Africa’s philosophy.

The staffs carried by the Spirit Medium, are some of the most profound, in terms of the quality and nature of their carving. They feature in particular the lion, snake and crocodile, symbols of transcendence pointing to the necessity for physical life to be lived in accordance with metaphysical principles, particularly the law of relationship.

Working with a powerful N’anga or Spirit Medium, in Murewa, NE Zimbabwe

This Sekuru, or respected elder, in Mudzi made a deep impression on me: he was preparing to leave the world of the living to enter the realm of the ancestors, and thus no longer spoke. He was passing on his role, before passing himself.

SYMBOL OF THE STAFF

An iconic symbol in Zimbabwean culture, the staff signifies the position of authority of the holder, particularly the Spirit Medium, the Chief or ‘tribal’ authority, and so on downwards, to the position of the man as head of the family. It is a symbol of the gravitas of authority, for the holder bears the responsibility of preserving cultural principles, of handing on such principles to the individual who will inherit his or her position on his passing. In African thinking, it was the significance of the position which was paramount, not the individual. For the position lifts the holder above the realm of the secular, and places him or her in an unbroken chain back to the founder of the tribe, and to the origin of humanity.

The staff has featured as a potent symbol in Zimbabwean cultures since the time of Great Zimbabwe, at least. Early European excavators of the late nineteenth century described such staffs found in the ancient graves around Great Zimbabwe, which they dug up for gold. ‘By his side, if he were a great man, lay his rod of office with the beaten gold head ... and with solid gold ferule six to eight inches long.’ Such gold artefacts were melted down into gold bars around the turn of the century, by a colonial company formed for the purpose, and no examples remain.

During the rise of nationalism in Zimbabwe the 1960’s, leading to the second Chimurenga or war of liberation, Joshua Nkomo, the traditional leader of the Ndebele people, was officially presented, ‘with a gano, bakatwa, and tsvimbo,’ (axe, dagger and staff), as symbols of the ‘spiritual rearmament’ that would be critical to the coming struggle. (Quoted from African Parade).

I loved photographing these ceremonial staffs in their context of usage : powerful sculptural works photographed in the natural light of the central living space which further charged their character ….

Contemporary Zimbabwean Art

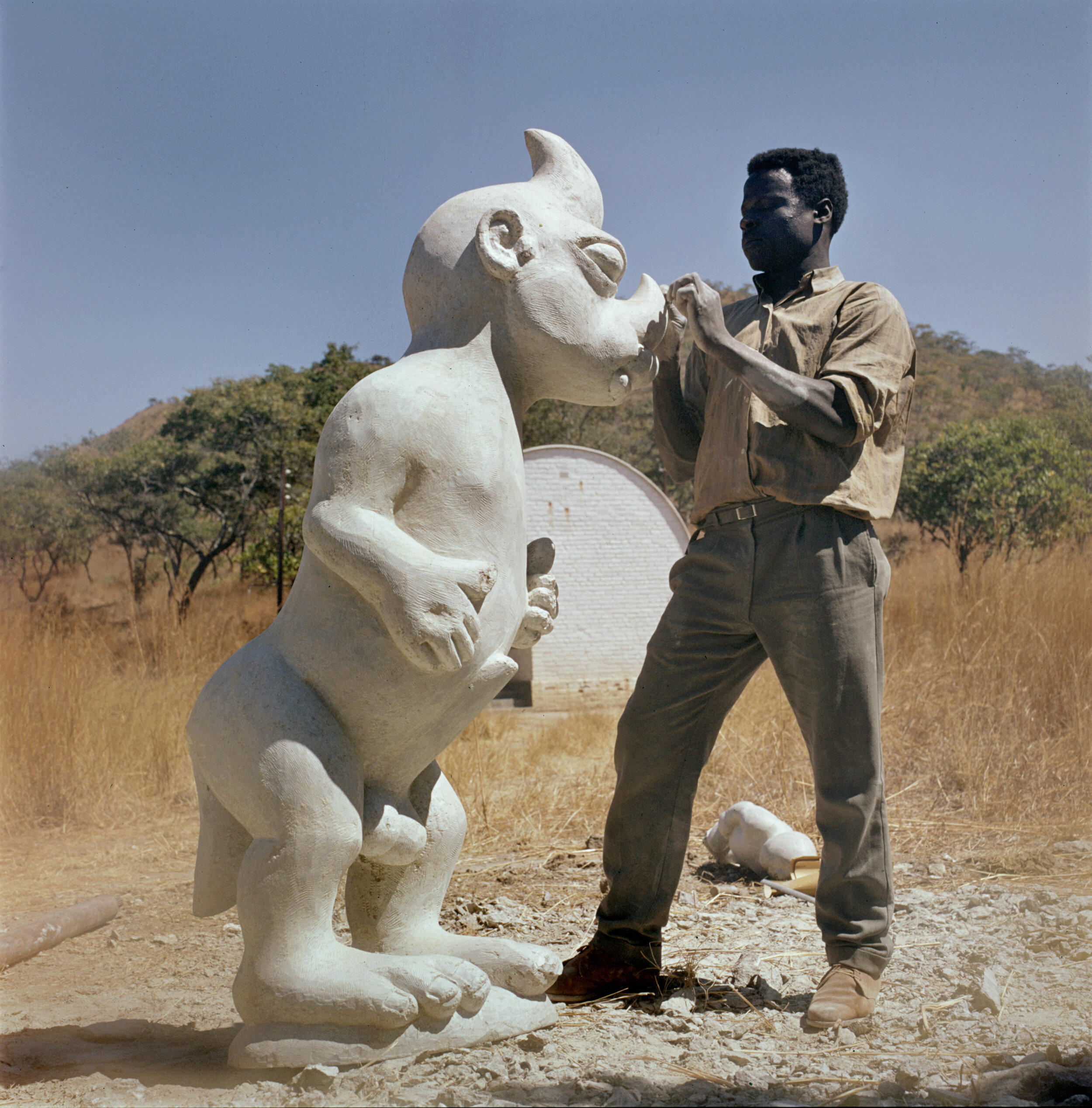

Zimbabwe has always been known as one of the sub-continent’s most creative countries. It is not surprising that the first contemporary art movement to come out of sub-Saharan Africa was from Zimbabwe, her sculpture in stone. Emerging onto the international art scene in the 1970’s, it was described at the time as ‘one of the most compelling art forms to come out of contemporary Africa.’ (Ray Wilkinson) Within a decade, it had been exhibited in major Western Museums, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Musee de Rodin in Paris, and the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London. The artists chosen medium was a ‘touchstone’ to a simultaneously past and present reality, the granite domes and outcrops of the country were part of the cultural and spiritual landscape. Serpentine was freely available, being quarried in the country, tools were made by hand, no machines were ever used, and it became the medium for black artists to express their own psychic identity in a milieu in which all things African, in the colonial milieu of the time, were regarded as inferior. The unforgiving medium of stone yielded to the ‘I -Thou’ relationship of African consciousness, of being at one with the rhythm of things. This was the elemental power of these early forms, and the reason it made such an impact on the international art world. Forms which expressed a powerful energy that was a statement of being, whether human, animal or even hybrid, being as simultaneously transcendent and actual.

Contemporary art survives only in collaboration with audience, patron, market, the relationships every artist must negotiate. The first Director of the Rhodes National Gallery, now the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Frank McEwan, came to the newly opened Gallery in 1957 straight from the art world of Paris and a close association with Picasso. Steeped in the aesthetic of the avant-garde of Paris, he recognized the same in the black artists of Zimbabwe, in a society polarized between African and European, and he opened a way for black artists that was not there for them before. The art critic Michael Shepherd wrote in Art Review of 1988, that on the passing of Henry Moore, the position of the greatest living sculptor had three contenders, and ‘all three’ were from Zimbabwe.

Portia Zvavahera, 2016, Embraced and protected in you, printing ink and oil bar on canvas, 210 x 400cm. Copyright the artist, courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg

It is not so easy to erase an aesthetic consciousness, an awareness of the deeper questions and dimensions of life, which was what drove the emergence of Zimbabwe’s stone sculpture. The same desire to express the human condition is behind a second contemporary art movement from Zimbabwe, making its mark on the international art world, the work of her young painters. These artists are speaking from their everyday experience of Zimbabwe’s spiral of disintegration. Their work strives to interpret who and where is the self, in a situation which has gone so far beyond the ordinary that it is not easy to describe in words. This time it is paint, photography, graphics, and found objects in a bricolage of township life, multi-media applied in bold gestural strokes and vibrant colour, which coalesce into personal metaphors, commentaries on meaning where meaning as a shared security has vanished.

Although not exhaustive, nevertheless the following artists are prominent in a remarkable body of painting coming out of Zimbabwe, Kudzanai Chiurai, Virginia Chihota, Misheck Masamvu, Gareth Nyandoro, Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude, Portia Zvavahera, Amanda Mushate, Admire Kamudzengerere, Lovemore Kambudzi, Richard Mudariki, Wycliffe Mundopa, Moffat Takadiwa. The Zimbabwean capital, Harare, worldly in its hustle and struggle, has become a mecca for ‘international gallerists and collectors’ to quote Valerie Kabov, its artists committed to succeeding on their own terms.

Bernard Matemera, one of the major 1st generation Zimbabwean stone sculptors, at work, 1975